There’s an arms race underway in artificial intelligence. Not between national governments or geo-political adversaries. This time the arms race is happening between private companies, big and small, mostly located in Silicon Valley, San Francisco and Seattle.

The CEOs of those companies just made a startling admission: they have no idea how to stop the escalation before they drive human society off a cliff.

When the CEO of the firm that is leading the charge begs Congress to intervene with regulations, we ought to take him at his word.

Sam Altman told Congress:

“My worst fears are that we cause, we the field, the technology, the industry, cause significant harm to the world. I think if this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong.”

How wrong? Just one week ago, many (but not all) of the leading AI researchers and CEOs signed a statement that compares artificial intelligence to nuclear weapons and pandemics.

There are good reasons to be skeptical of the hyperbolic claims made by technologists, but today I want to make the case that we should take them up on their proposition.

It’s time to regulate the hell out of artificial intelligence.

Tech CEOs may be bullshitting, but don’t let that slow down regulation

There is no evidence today to support the claim that AI presents an existential threat to human society. Some people suspect that this a humblebrag by AI leaders, puffery intended to impress investors and scare off rivals. “Look how powerful we are.”

It’s quite possible that the dire warnings from tech CEOs may be shark repellent intended to keep legislators at bay. Their comments resemble the don’t-try-this-at-home rhetoric dished out by the captains of the finance industry, essentially: “What we do is so incredibly complicated that we are the only ones capable of handling it safely.”

Even if the tech CEOs are exaggerating the existential threat, there is plenty of evidence that AI does cause certain kinds of damage today. The widespread use of algorithms has already created pernicious problems that have been well documented. The track record here is poor. The tech firms have been warned about these problems for years, but they have failed to solve them.

The current real (not hypothetical) problems include embedded racial bias, gender bias, bias in hiring, judicial sentencing, and policing.

Fretting about dramatic existential threats is a distraction that tends to overshadow these real-world problem cases.

This is a failure of industry self-regulation. Another justification for regulation.

The economic dynamics that propel the AI arms race are also problematic. Like other network-based technologies, AI benefits from the increasing returns to market leaders. A handful will win; a large number will not. Those who lose will absorb the costs of disruption. This winner-take-all dynamic is very likely to exacerbate income inequality. So it seems very likely that AI will ultimately cause further concentration of wealth and power in a few hands. Not a great outcome for a pluralist society.

And there may be a deeper problem, an attitude problem that is shared by many leading AI computer scientists. When confronted with the litany of current problems with already-deployed AI, they often respond by minimizing them: “Those problems are easy to fix, instead we should focus on the much bigger existential threats presented by AI.” As if the likelihood that certain problems can be fixed means that the problems already have been fixed.

Not enough has been done to address either set of issues, neither the real problems of bias that are well documented today, nor the low-probability hypothetical problems that may emerge in the future.

All of this leads us to conclude that:

The AI firms are not particularly reliable when it comes to making an accurate assessment of the risks associated with their products, and

They are the least likely group to propose a regulatory framework that will govern their conduct in society’s interest.

That’s why it falls to the rest of us to deal with this issue.

Each of us must begin thinking about a regulatory framework; otherwise we will be obliged to meekly accept whatever we are given by Congress. The stakes are too high.

I am no expert on regulation but that won’t deter me. I reject the argument that only certain people are qualified to make decisions about a technology that will soon penetrate every industry and every decision process.

We will all be affected. We all have a stake in the outcome. That’s why we all need to participate in the process of forming sound policy to govern this technology.

So let’s get busy.

An useful futurist skill is to envision potential scenarios, consider the consequences, and then propose mitigation strategies. Start by asking yourself some questions.

What do you care about? What do you want to preserve? What outcome do you wish to avoid? If we focus on desired outcomes ,and if we manage to define the values that we want to protect, then we can work out the precise regulatory mechanisms later.

Regulating AI is a daunting task. There are complex questions about data usage, privacy, security, the terms for using training data, access, ownership, business model, taxation, and open source. Each of those topics will take us down a deep rabbit hole. We’re not going there today. Before that, we need to get clear about broader values.

Below I’ve made a list of some broad principles that I think may be necessary to make regulation of any of the specifics effective. I’m sure that I got many things wrong, and perhaps some of what I’ve proposed is unworkable. That’s why I welcome your comments and constructive suggestions. Let’s get in the habit of helping each other formulate better thoughts.

Treat AI like nuclear weapons.

In last week’s vague-but-scary pronouncement, the leading AI researchers and CEOs made an explicit comparison to nuclear weapons. So let’s use nuclear safety as the standard.

If these leaders truly believe that these products have the potential to be as destructive as nukes, then we probably ought to manage AI the same way that nuclear weapons are handled: A United Nations resolution to create a new international regulatory agency with the power to conduct unannounced spot inspections in any site where AI is being trained, developed or deployed.

Under such a scheme, every company that wishes to conduct research or productize AI could be required to obtain a license from the UN agency. To maintain the license, participating firms must file regular reports, cooperate with inspectors, conform to compliance rules, document procedures, adopt and enforce a mandatory code of conduct, maintain a process for whistleblowers, and pay fees.

Every licensed AI firm will be subject to constant ongoing safety audits conducted by an independent agency. The findings should be made public. Companies who are found to be non-compliant could have their licenses suspended. Likewise, the deployment of products with demonstrable flaws and biases might be suspended.

The annual cost of renewing the license should be sufficiently high that the AI firms cover the entire cost associated with setting up and running this new regulatory agency.

Universities that conduct AI research should also be subject to agency review. Their continued access to funding from the federal government could be subject to compliance.

Make blunders more expensive as a deterrent.

Our consumer economy has a fatal flaw: sometimes when private industry launches a completely new product, people get injured. Sometimes a responsible company will issue a recall of the product. But in other cases, the company will choose to make profit by continuing to sell the dangerous product, regardless of externalities. This pushes the costs of the problem from the private sector into the public sector.

Tobacco and lung cancer. Automobiles and carbon emissions. Social media and bullying. Guns and mass shootings.

In each case, there is ample evidence that the companies were aware of the damage caused by their products. Despite that, the firms continued to press forward aggressively with sales and marketing, making at best cosmetic adjustments to mollify critics and keep legislators away.

In each case, private companies managed to pocket profits while shifting the cost to society, a practice known as the “privatization of profit and the socialization of costs.”

Perhaps the most extravagant example of this was the Federal government’s 2008 bailout of big banks after a decade-long spree of highly profitable sub-prime mortgage lending that left the entire financial sector in a precarious situation. Despite ample evidence that mortgage underwriters had sidestepped rules and regulations in pursuit of more loans, many of the firms that benefitted most from lawlessness were bailed out by government. Meanwhile the hapless homeowners who learned too late about fine print in their balloon mortgage contracts were were wiped out.

The common thread running through all of these examples is that private industry is incapable of restraining itself, especially when there is reason to believe that the government will provide a bailout. After all, private corporations are optimized to generate profit. Self-restraint does not comport with Milton Friedman’s Prime Directive.

It’s rare to see governments strike back at greedy private companies that inflict massive damage to society. One example of clawing back profit can be found in the lawsuit filed by 23 state attorneys general and 2000 municipal governments against the makers of OxyContin. The settlement required Purdue Pharma to disgorge $12 billion and its owner, the disgraced Sackler family, to hand over a further $4.5 billion. At stake in this matter were the massive sums paid by government for health care treatment for the people who were addicted to OxyContin.

The problem with pursuing recourse through the courts is that it is expensive, uncertain and subject to years of delay and appeals. This is inefficient, and the penalty comes many years too late to deter the wrongdoing. The multi-billion settlement may help the governments recover some, but not all, of their costs. However those funds will do nothing to help the 2 million people who were addicted to OxyContin, nor the 400,000 who died as a result.

Why not flip this sequence around? Instead of chasing malefactors years after the fact, why not make the firms put up a security deposit up front? If the firm makes a tragic blunder, then they forfeit their deposit. Deterrence is more efficient than retribution.

As the statements made by the leaders of the AI companies make clear, there is a broad but unquantifiable risk of a major disaster that may be caused by AI. Why wait to find out how bad such a disaster might be?

Moreover, why should society shoulder the burden of worrying about this risk? Let the AI firms deal with it. Knowing upfront that a blunder will cost them their deposit may cause AI firms to proceed with extra caution.

One goal for regulating AI may be to ensure that the costs from any disaster are not borne by taxpayers, but rather by the companies that are pushing AI. This could be accomplished by requiring each firm that wishes to engage in licensed AI research to post a bond large enough to offset the cost of damage in the event that their technology goes haywire.

Firms the size of Alphabet and Microsoft might be required to post a $250 billion bond for AI Disaster Relief that would be forfeit in the event that any safety guidelines are ignored.

Perhaps, given the nature of the threat, $250 billion is too small.

For smaller companies, a smaller bond proportional to scale might be necessary in order to maintain competition and some preserve some space for startup companies.

Investors will decry such a security deposit, arguing that it ties up capital needlessly, stifles competition and favors big companies. Perhaps the bond could be designed to address some of those concerns, but let’s bear in mind that the point of AI regulation is to mitigate the risk of disaster, not to enrich private investors.

If such a security deposit caused the speculative investment frenzy to fade, that might not be undesirable. Cooling off the market and slowing down the rate of deployment will reduce the risks introduced by the pellmell AI arms race. Perhaps this would satisfy the 31,000 experts in the field have already published a call for a moratorium.

The operating principal in this concept is proactive: to push the risk of catastrophic costs onto the private firms and their investors before mistakes are made.

Unlike banking, this technology is not yet systemically vital to the economy. So why should the government be looked upon as a backstop?

The current boom in AI investment tells us that investors anticipate massive gains in the future. Let them bear the cost of any potential downside risk.

Make directors personally liable.

One way to ensure that the Board of Directors is actively engaged in meaningful supervision of the management at AI firms is to remove the protections that limit their personal liability in the event of a mishap.

Financial penalties and jail time for board members who neglect to exercise diligent oversight may be an effective way to shift the burden of monitoring compliance from government to the firms themselves.

This would probably lead to a booming new industry of compliance auditors for AI regulation. Not a bad outcome for AI safety.

It would also likely cause a reshuffle of board members at many companies. Good riddance. The world does not need investors who goad management to take bigger risks with AI; it needs prudent governance.

Make the AI firms fund insurance for disaster relief.

In March, the run on Silicon Valley Bank and the subsequent collapse of three regional banks provided another example of the tendency of CEOs to lobby for weaker regulations while pursuing risky gambits.

One thing was unusual. The government let the SVB fail instead of bailing it out with taxpayer funds. Investors were wiped out. The incompetent managers lost their jobs. This is the way it is supposed to work.

Depositors, however, were made whole. The federal government backstopped all deposits. Remarkably, this included even those who had deposits that exceeded the $250,000 limit per account of FDIC insurance coverage.

The Federal Depository Insurance is funded by the participating banks, not by the taxpayers.

Derisking AI is not perfectly analogous to insuring bank deposits, but there might be a useful model in FDIC for an approach to self-funded risk management in artificial intelligence. An insurance fund to mitigate disasters, paid for up front by the companies in the sector. This might come in addition to, or instead of, the security deposit scheme described above.

Such a shared-risk model could also have the desirable side effect of causing AI companies to keep closer tabs on each other’s practices, and report risky behavior before the problems arise.

Treat humans with respect

It’s dismaying that it is necessary to make this point. Humanity gets abstracted away from the debate about training data for large language models.

That “training data” is not an inert natural resource lying fallow that was discovered, like a copper deposit in a mountain. Nor is it the data smog that is collected by tracking human behavior.

The data in question the result of conscious, careful human effort. It is created by us. In many cases, it is the creative achievement of humans working at the best of their ability. It consists of literature, fine art, lyrics, poetry, laws, scientific reasoning, academic proofs, and other feats of intellectual effort. And even if some of it is just tweets and casual comments on social media, all of it has genuine value: economic value, cultural value, artistic value, and civic value.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that what AI scientists refer to as “training data” is the fabric of human society.

100% of the data used to train AI is created by humans.

Every society respects long-established practices to govern the way humans can use the intellectual property generated by other humans. Why not for machines?

When humans borrow ideas and cite the work of other humans, their conduct is typically governed by three Cs: consent, credit and compensation. It might not be strictly necessary to give all three in every usage scenario, but that’s where a fourth C comes into the equation: courtesy.

The AI companies have acted without even the slightest professional courtesy towards human creators. No credit, no compensation and certainly no consent.

Smash and grab.

When every visual artist, author, columnist, influencer, blogger, photographer, screenwriter, legal writer, and software developer woke up to the fact that their work had been strip-mined to train a large language model, they were justifiably upset. When they later learned that those LLMs would be deployed in for-profit services that could someday render human expertise obsolete, they got angry.

They are right to be angry. This must be addressed in AI regulation.

It may be true, in a narrow legalistic sense, that what the AI companies did when training their LLMs is not technically copyright infringement under current laws. That’s why these firms might not be legally obliged to pay a licensing fee or royalty to the artists whose work they borrowed. Greater clarity will come soon via a series of lawsuits now making their way through the legal process. Admittedly, the drafters of current copyright laws did not foresee a time when a machine can be inspired by a human work and generate its own content.

Which means this is yet another area where new regulation should be introduced. Given the expectation that AIs will interact with humans in every facet of society, from the classroom to the hospital to the office to retail, we need to establish clear boundaries.

This may sound complicated, but it isn’t. The current approach to user data on the Internet is fundamentally disrespectful: it consists of data strip mining without consent. Humans are tracked and surveilled constantly with or without permission, with or without awareness, without any compensation.

That’s problematic when we are dealing with Facebook or Instagram. But when we are dealing with an autonomous system that can determine whether or not we qualify for a loan or a job or place in a university, it is grossly inadequate. This must be fixed, otherwise we will be stuck dealing with contemptuous AI systems that treat humans like data.

AI must be required to treat humans like humans, not like data.

AI regulation must restore and preserve human dignity. This is the direction that the Biden Administration is heading with the AI Bill of Rights.

I have been influenced by the writing of Jaron Lanier on this topic, especially his thoughts about Data Dignity.

Transparency

No more black box. Too often, when one asks how a generative AI system arrived at a result, the answer is “We don’t know, exactly.”

It is also infuriatingly difficult to understand how closed models train on data.

This is untenable. It’s not difficult to imagine scenarios in which it will be necessary to expose how an AI works to determine liability, provenance, derivative works and so on.

Likewise, if our goal is to align AI ethics with human values, then humans will need some way to verify the steps in the reasoning process used by an AI.

As Roman V. Yampolskiy, a professor of computer science at University of Louisville, wrote in his paper Unexplainability and Incomprehensibility of Artificial Intelligence:

“If all we have is a ‘black box’, it is impossible to understand causes of failure and improve system safety. Additionally, if we grow accustomed to accepting AI’s answers without an explanation, essentially treating it as an Oracle system, we would not be able to tell if it begins providing wrong or manipulative answers.”

Transparency may be the solution. At a minimum it will be useful to be able to interrogate the decision-making process followed by the AI as it delivers a result. What factors led to the decision? Which factors counted heavily? Which were ignored? What sources were used? What reference points were missed?

It may be difficult to obtain an itemized step-by-step summary of the AI decision-making process, but the alternative is worse. A black box reasoning process that cannot be interrogated is a process that cannot be trusted.

Disclosure and labelling of AI generated content

All AI-generated content must be labelled clearly. Otherwise, the risk is great that social networks will be flooded by persuasive AI-generated propaganda.

On this topic, most people seem to agree. There are questions about how to monitor compliance and how to deter cheating.

What form should the warning label take? A subtle transparent watermark? A small mark in the corner of a video?

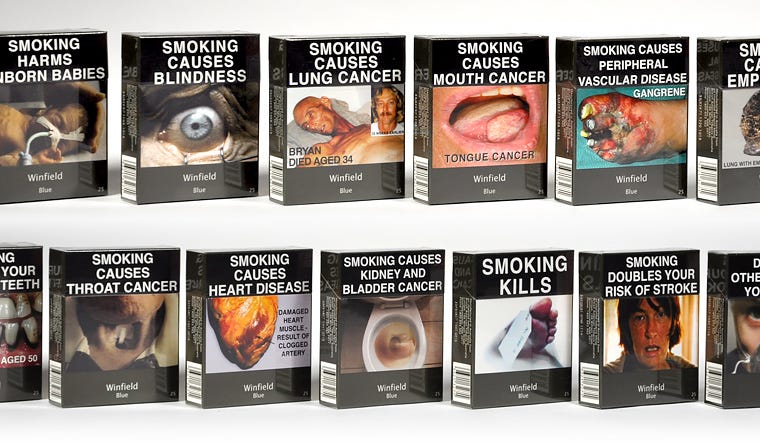

I’d propose that we go further. Consider the way tobacco products are labeled in the UK and Australia and several other nations. No-brand packs that show vividly the health hazards of consuming tobacco have been proven to diminish consumption.

Why not insert an unskippable pre-roll graphic that sets forth the perils of consuming deep fakes and computational propaganda? Why not impose a penalty on anyone who attempts to strip the warning label from AI-generated content, the same way people can be penalized by the FBI for stripping the copyright notice from a movie?

This might seem a tad harsh but even Geoffrey Hinton, the so-called Godfather of Artificial Intelligence and pioneer of neural networks, sees the coming flood of fake news as a major concern that could destabilize society.

Why permit that flood to happen without taking some step to prevent it? Why not take action now to deter people from trusting and disseminating AI-generated content?

Free speech advocates might object, but this measure would not infringe the right of any human: these constraints pertain to content generated by a machine intelligence. This is an excellent time to draw a clear distinction between the speech rights of humans and those of machines.

Thanks for reading these thoughts. This is not my usual subject. I’d welcome constructive feedback from readers.