Patents and privilege: the original sin of copyright

The sixth article in a series about Copyright in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence

This is the sixth in a series of articles about copyright and generative Artificial Intelligence. The first items addressed the collision between generative AI and copyright, and explored why society needs copyright laws.

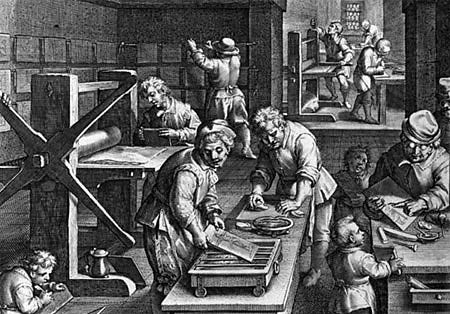

This week, we are completing a short account of the history of the printing press and the mechanical reproduction of books to understand how technology can accelerate the disruption of a long-established order. This helps us get to the reason why copyright was necessary.

The third article explained how the printing press enabled rational discourse and public debate to accelerate beyond the control of the Catholic Church. The fourth missive described how the printing press enabled the leaders of the Protestant Reformation to defy the Pope. This led to the ferocious wars of religion that consumed Europe for much of the 16th and 17th century.

In the fifth article, we charted the path of the secular state. After the Thirty Years’ War, the nation-state began to dislodge the Church from a position of control over the information landscape. In its place, kings introduced something new: a literate class of bureaucrats to supervise and govern political discourse. Ever since, bureaucracy has been a feature of government.

Forerunners of Copyright: how monopoly, patents, privilege, and cartels fostered corruption

Many European monarchs shared a bad habit: a penchant for bestowing monopoly rights on friends and favorites.

This habit grew from the foundational principles of feudalism, an economic system that every ruler understood innately because it was the basis for their power.

The earliest European monopolies were based on property rights. This long tradition is likely to be the origin of the metaphorical concept “intellectual property rights.”

The first monopolies were royal charters issued by feudal lords to their most loyal subjects, granting to the nobility the right to all revenue from land grants, in exchange for service, typically as a knight in the king’s wars.

If the vassal were deemed disloyal, or otherwise fell afoul of the monarch, then the land grant could be revoked. This precarious arrangement was the basis of feudal society. It tended to keep the nobility aligned with the king.

(Eventually, royal caprice provoked the nobility into demanding parliaments and the separation of powers as a check on the caprices of an absolute ruler, but that is another story).

Around 1500, royal charters began to extend beyond land grants into the rapidly-expanding domain of private enterprise. Why should a king limit himself to land grants when he could profitably grant monopolies over domains, such as trade, exports and manufacturing, too?

The royal patent devolved into a system of patronage. Monarchs, princes, and emperors found that issuing royal patents was an easy way to fill their coffers; and it enriched their allies and gained new supporters among the gentry.

Book publishers were no exception. Rulers used the lure of monopoly to gain leverage over publishers.

By granting a monopoly right that reinforced the business model of publishers, the monarch was able to compromise the fiercely independent publishers. Some monarchs went further, deputizing their publishers and printers to enforce the guild system. This was an easy way for the state to monitor illicit printing presses and thereby limit the expression of seditious ideas.

This arrangement left the publishers dependent upon the whim of a monarch who could (and often did) revoke privileges. The right to print could be withdrawn capriciously, on a whim. That caused publishers to tread lightly, avoiding any offense, staying carefully within royal guidelines, and refraining from publishing heretical, blasphemous, skeptical, or seditious concepts. Publishers also had an incentive to report anyone who violated these rules.

In every case, such privileges led to corruption, bribery, and abuse of power.

The earliest forms of copyright were used not only to protect intellectual property, but also to stifle competition. In each of the 200 cities where printing gained traction, cartels arose that used permission to print as a means to exclude rivals and concentrate supply into fewer hands.

In 1469, the Republic of Venice introduced the first proto-copyright. The terms of these early rights varied considerably, but the essence of such an instrument was the creation of a time-limited monopoly that enabled the publisher to recover the initial investment and earn a profit for a relatively short period ranging from two to 14 years.

Initially, such “privileges” were granted directly to the authors of books; but soon, authors were displaced by the publishers of Venice, who garnered most privileges for themselves. That’s when the Venetian publishers formed a cartel that monopolized printing in the Serene Republic. They sought to make the privilege perpetual.

In their greed, the Venetian publishers eventually warped the copyright process, turning it into a tool to thwart newcomers and stifle competition. Printer-publishers began to register long lists of book titles pre-emptively, including books that had not yet been written, to crowd out would-be rivals. Their goal was to secure monopoly privileges before publication had even begun. In 1517, the Senate revoked all privileges and stripped the issuing authority from the College that had been corrupted by the publishers.

This attempt to consolidate printing power occurred just as Venice was emerging as the leading hub for printing in Europe. From 1469 to the end of the 15th century, 153 printers in Venice had published 4,500 titles, at least 15% of all books published in Europe. During the 16th century, the number of printers quadrupled and their output soared to 150 editions each year, with average runs of 1000 copies and as high as 3000.

The Venetian printers’ attempt to co-opt the privilege is an early example of the difficulty of establishing an impartial regulatory system that imposes constraints on free trade in order to protect intellectual property rights. The process demands impartial and transparent governance, otherwise it typically will end mired in corruption.

Today we refer to this type of corruption as regulatory capture, whereby the regulated parties seize control of the regulatory apparatus.

Modern readers may smile when they read about the Venice affair; but the smiles may turn to frowns when they consider that the US Copyright Office today is similarly captured. The current Register of Copyright, who was previously TimeWarner’s top IP attorney, recently hired the Walt Disney Company’s former Deputy General Counsel to serve as the Copyright Office’s new General Counsel. Some things never change.

Why it matters:

From the beginning copyright has always been enmeshed with the concepts of monopoly, control, censorship, and profit. Publication laws became one of the principal mechanisms for imposing constraints on free speech in every nation in Europe, and elsewhere. Some of these laws remained in force until the 1970s.

There was nothing subtle about this process. It was overt. The earliest forms of proto-copyright protection were referred to “monopolies” or “privileges”. Groups of favored printers who were granted monopolies soon formed professional societies and guilds to protect their privilege; rival printers were excluded and outlawed.

Today, the laws have changed: perpetual monopolies are no longer granted, but regulatory capture persists, ensuring that copyright owners have the power to shape the rules in their favor, and strong economic incentive to ensure that lawmakers favor their cause.