Discover more from The Owner's Guide to the Future

The movie studios should be worried about AI

At least the screenwriters understand what they are up against

This is the third article in a series about artificial intelligence and the strike by the Writers Guild of America (WGA).

One recurring theme that I’ve gleaned from the press and reader commentary is the pessimistic view that the Writers Guild strike is futile.

As explained in my previous report, I disagree.

According to the Pessimistic View (for short, the PV), the WGA strike will backfire, because it will hasten the demise of screenwriters.

There are three parts to the PV argument. But here’s the thing. The PV argument is spurious. And yet, for entirely different reasons, I do believe that the strike saga will end in tears because the writers are doomed if they strike and doomed if they don’t.

Let’s break this down. We’ll begin by dismantling the PV argument, and then I’ll turn to the much bigger issue, which is that the studios should be panicking about AI, not the writers.

First, the Pessimistic View opines, the WGA strike will inflict economic harm on the studios: this damage will greatly reduce the studios’ ability to pay higher fees and improved residuals.

Second, the PV claims, the demands of the writers, if granted, will raise costs permanently, which will further destabilize the entire motion picture economy and thereby upset the delicate balance of the creative ecosystem.

Third, by withholding their labor from the marketplace, the writers will stimulate demand for artificial intelligence as a substitute.

To me, these three PV arguments sounds like this:

The strike is a self-inflicted head wound because it harms the companies that pay the writers. Ergo, the writers would be better off if they never went on strike in the first place. By this logic, no worker should ever demand a raise.

Just by asking for a raise, the writers introduce the possibility of annihilating the entire entertainment economy. A few thousand strikers have the power to destabilize a massive global industry that is wildly profitable.

By striking, the writers have justified the studios’ evil plot to replace human talent with machines. They asked for it.

In my opinion, this whole argument stinks.

Missing from it is the fact that the screenwriters had no choice in the matter.

Doomed if you do, and doomed if you don’t

If you happen to be doing business with another party who uses a contract loophole to underpay you and forces you to accept lousy conditions that degrade your expertise, then you have no choice but to renegotiate for a better deal.

It really is that simple. Anything less amounts to capitulation without a fight.

Professional writing talent has unique value. Scarcity increases its value. The only people who can present that pricing to the market are the writers. And that’s what they are doing.

In the TV industry, when it comes to fixing unfavorable deal points, the adage goes, “We’ll get ‘em on the renewal.”

The contract between the writers and the studios had expired. It was time to cut a new deal. Contained in the old contract were terms and conditions that were plainly unfavorable to the writers. They had sucked it up throughout the term of the contract, all the while letting the producers know that they planned to seek better terms when it came time for renewal.

But during the latest round of negotiations, the WGA got nothing. That’s because the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) did not engage in a meaningful way on the key issues of residuals, pay or writer’s rooms. Most insultingly, the AMPTP simply brushed off the writers’ concerns about the use of artificial intelligence with some vague noises about attending an undefined meeting in a year’s time, by which time AI would be firmly and inextricably embedded in the screenwriting workflow. As everyone knows.

The whole debate between the WGA and the studios (represented by the AMPTP) boils down to a few key points about pay, residuals, staffing, respect and a demand for clearly-defined guardrails around the use of artificial intelligence in screenwriting.

When you are negotiating with a counterparty that refuses to engage on the points that are most important to your side, then you don’t have much choice. You need to drop the bomb. And that’s what the WGA did on May 2.

You can’t blame the Writers Guild for doing exactly what a union is supposed to do. Namely, withholding their labor from the marketplace to improve their bargaining leverage.

This is why I think the Pessimistic View is bogus. The whole point of a strike is to put economic pressure on the employer by bringing their business to a halt. And yes, a strike is also costly for those on the picket line and those who refuse to cross it. That is why a strike is the last resort, not the first option. The union contemplated these consequences and then 97.8% of the membership voted in favor of proceeding with the strike.

And finally, the point about hastening the deployment of artificial intelligence while the strikers are picketing is pure horsepucky. Today no generative AI system is capable of replacing a professional screenwriter. Anyone who tells you otherwise is hallucinating worse than ChatGPT.

The Pessimistic View tells us nothing useful about the WGA strike, but it does reveal how some Americans have internalized the neoliberal rhetoric that has dominated political discourse in the post Reagan era. It tells us a lot about how deeply many Americans have been indoctrinated by the mythology of the free market and the primacy of Big Business over labor.

That represents a significant departure from the past. Prior to the Reagan Administration, the US had plenty of strong labor unions with widespread support. Unions commanded respect from most working people.

I recall clearly as a child growing up in 1970s Cleveland that my family wouldn’t set foot across a picket line, nor would any of our friends and neighbors. Most of them were proud members of a labor union.

That began to change during the Reagan era. Beginning with breaking the Air Traffic Controller strike in 1981, the US has systematically weakened labor unions and then degraded protection for workers. Many factors propelled this process, including the interlocking trends of globalization, the growth of shipping containers and global supply chains, NAFTA, the rise of China as the world’s workshop, and anti-union policies.

It is no coincidence that we can trace the origin of wage stagnation to the Reagan Era, too. Income inequality began to rise when Big Labor got kneecapped.

Today the century-long labor movement that spanned the 19th and 20th centuries seems like a chapter from ancient history, not events in living memory. Did workers really fight pitched battles against private armies of gun-toting Pinkertons outside locked factories? Yep, they sure did. Were workers massacred and jailed for attempting to strike for better wages and benefits? Yes, that happened.

But that was so long ago. After four decades with very few strikes, the struggles of the labor movement seem to have faded from our collective memory. A growing number of Americans seem unable to comprehend the purpose of a labor union and how union negotiations work. I wonder if this is because so many people today are so desperate to have any job at all that they resent those who have the temerity to agitate for better pay and better conditions.

If home viewing audiences truly feel a sense of solidarity with those who write the shows they love, they certainly haven’t demonstrated it yet. It remains to be seen whether Netflix will lose more viewers who quit in protest over password-sharing rules than those who cancel the service in solidarity with the WGA.

But that’s not the only reason I find the Pessimistic View bogus.

The Studios can afford to pay what the writers want

There’s a second point: the demands of the Writers Guild are surprisingly modest. They certainly won’t break the bank or disrupt the (rich) economics of media production.

When it comes to pleading poverty, the movie studios deserve to win an Oscar for best performance. (That lame joke proves that I am unqualified to be a member of the WGA).

Studios are masters of striking a deal with an attractive revenue share on the backend, called the “net,” then cooking the books to reveal later that the blockbuster film with massive box office success actually generated zero profit after marketing expenses. Not one cent, sorry!

As the saying goes, “There is no net.” Nothing new about that. It’s standard operating procedure, known to the rest of us as “studio accounting”.

The people who direct this creative approach to accounting happen to be the same folks who call the shots at the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, the group that is negotiating against the Writers Guild.

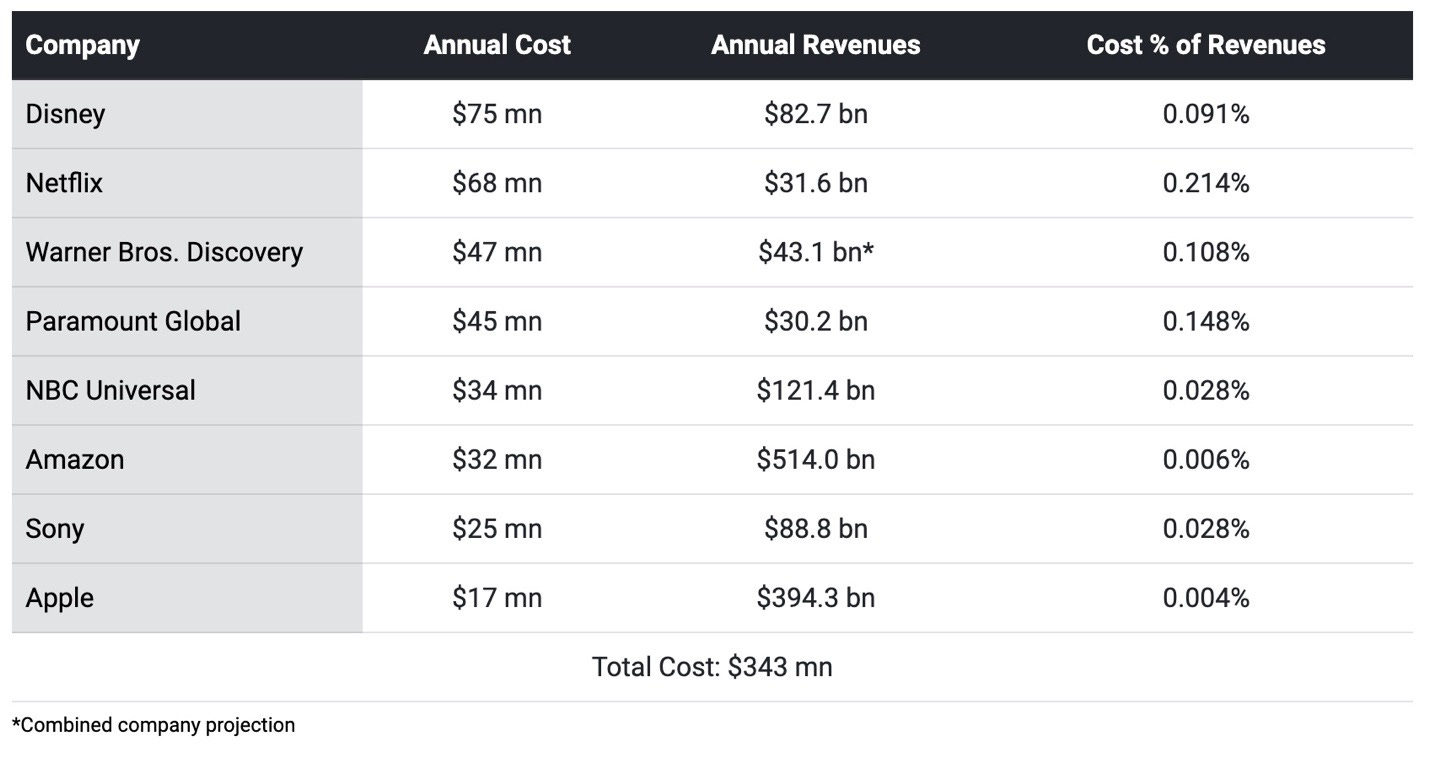

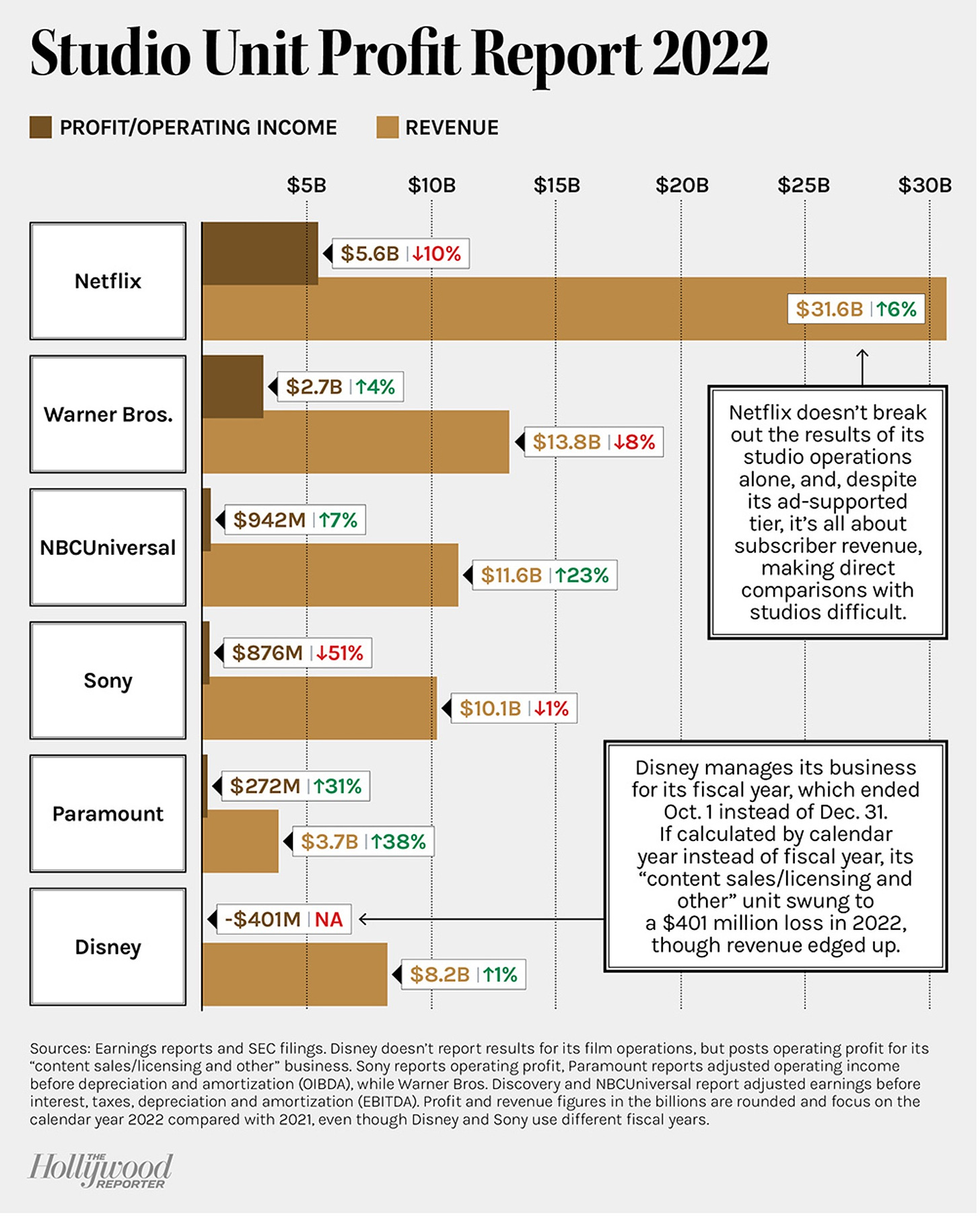

A similar kind of bookkeeping legerdemain occurs when the studios claim that they cannot afford to pay writers a penny more at a time when billions of dollars in revenue is flowing into their vaults from projects written by WGA members. Profits have recovered from the pandemic lull. Studio executive salaries are at an all-time high. And these guys are too broke to give a writer a raise?

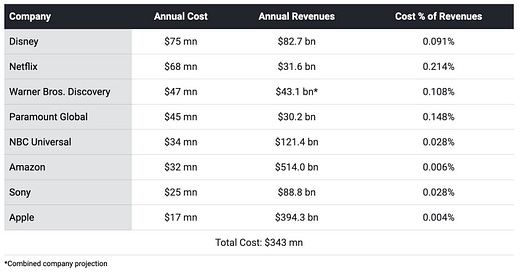

The WGA maintains that its demands in total amount to $429 million, of which only $343 million would be payable by the 300+ member companies in the AMPTP.

To put those demands into perspective, 2022 domestic box office from theatrical films was a whopping $7.8 billion. International was $25.7 billion. And that’s just the box office earned at movie theaters; it does not include revenue from streaming, television, cable, and other sources.

For each major studio except Netflix, the WGA demands would add up to less than 0.2% of revenue. For smaller producers, this might be costly but for the big giants like Apple, it amounts to a rounding error.

I feel obliged to disclose that I got these figures from the WGA website. An anonymous studio executive, according to Deadline, dismissed these figures are “baseless and just made up to gin up their membership and make for provocative headlines.”

Whatever.

I’ve seen estimates that peg the WGA ask as high as $650 million but this difference does not matter. The point is that the sum total of WGA demands is very small compared to the billions of dollars of profit raked in by the studios.

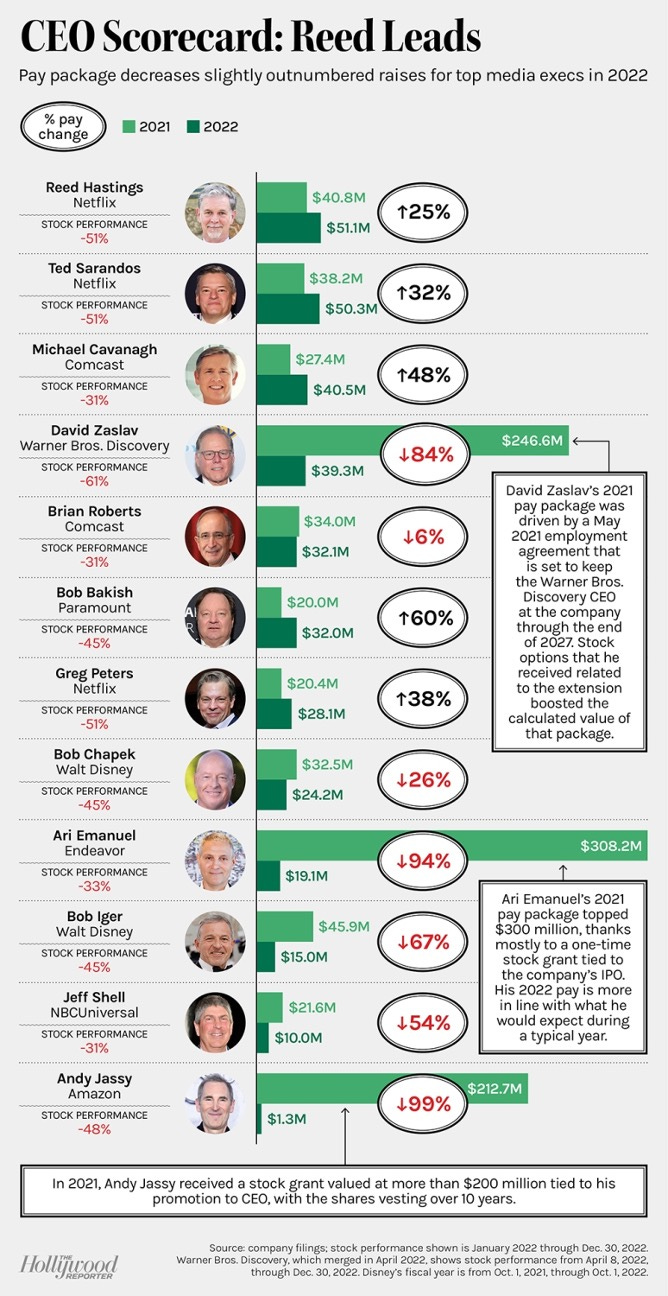

To put the writers’ demands in context, just consider how much the studios pay their executives. The combined salaries of the CEOs of the AMPTP member companies exceed the total amount demanded by the WGA. On average in 2022, media company CEOs earned $32 million in a combination of cash and stock. Several are paid more than the $50 million a year.

Bear in mind that none of these gentlemen (yes, all men) would earn a dime without the stories created by writers.

Just one executive, David Zaslav of Warner Bros Discovery, earned a whopping $232 million in 2021. For clarity, I should point out that the bulk of Zaslav’s prize was conveyed in the form of stock, not cash, in connection with a contract extension following Discovery’s acquisition of Warner Media when it was spun out of AT&T.

Since then, Zaslav’s pay package has dropped to a modest $39 million.

It’s not a great look at a time when the the share price is plummeting and media companies are firing employees by the thousands and workers are on strike.

Here’s the CEO pay scorecard:

The contrast between the amount of cash and stock showered on executives and the devaluation of the screenwriters is a vivid illustration of income inequality. There is only way to pay an executive tens of millions of dollars: that is by withholding pay from thousands of workers. This is just a question of how to divide the profit.

The history of labor in the USA from the 1870s to the 1970s consisted of a long, often violent struggle for a more equitable distribution of the profit to the workers. During the past 30 years, many of the gains made during this struggle have been erased: today’s income inequality is comparable to income inequality that defined the 1920s. The Jazz Age was splendid for a privileged few and widespread misery for the majority.

We’ve lost a century of progress.

This ought to be a major political issue. After all, income inequality destabilizes working families, neighborhoods and ultimately damages democratic society. As Supreme Court justice Lewis Brandeis said, “We can either have democracy in this country or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.” According to Bloomberg, 30 years of income inequality has shrunk the national economy by $23 trillion.

What’s odd about this situation is the bored silence of most workers in the US. They should be concerned, but they remain silent. Too busy binging on Netflix?

As I wrote last week, nearly 40% of the US workforce is freelance. Those 73 million independent workers live precariously. They function as a kind of human shock absorber for the American economy, absorbing the punishment when business must react and readjust. The dynamism of the American economy depends in large part on this vast freelance and independent workforce. They get no benefits, no insurance, no bonus and no retirement or pension plan. They ought to care more about what happens to the writers.

So, I am deeply skeptical of the Pessimistic View about the WGA strike because (a) it mixes up cause and effect, and (b) it remains oblivious to the biggest socio-economic trend of the past 50 years.

And that’s not all.

I have a third reason for rejecting the Pessimistic View: it is not pessimistic enough.

The Pessimistic View rests on the assumption that the companies sitting across the table from the WGA are unified. In previous negotiations in an earlier era, that may have been accurate, but it’s far less true today.

What the PV argument fails to take into account is the fact that the writers are striking against several different types of companies. Four kinds, if you include TV networks and independent producers, but let’s set them aside for now because what really matters are the big studios and big streamers.

A hardware company like Apple has very little in common with Disney. An e-commerce retailer like Amazon (which owns the residue that once was MGM) has nothing in common with Warner Bros Discovery. A pureplay online giant like Netflix shares only the economics of streaming with Paramount, and none of Viacom’s legacy baggage.

There are a lot of ways this could play out. Big tech could (and might) opt for an outcome that will not favor the old school studios.

Let’s start with Netflix. Almost entirely dependent a single revenue source, namely subscriber fees, Netflix is naturally the most hawkish about keeping a lid on streaming costs. This includes squeezing residual payments to writers and reducing the number of writers on each show. Also, as a closed system, Netflix has no desire to reveal accurate data about the number of viewers for each show: this makes it difficult for the agents and managers of independent artists to calculate residual payments. Some grumbling in Hollywood blames the whole strike on Netflix’s intransigence on these issues which form the core of the WGA complaint. The company looks like a villain in this drama. Netflix’s stubbornness may hurt the old studios that sit on the same side of the bargaining table.

Meanwhile, giant technology firms like Apple and Amazon share little or no strategic alignment with movie studios owned by media conglomerates. It seems likely that Apple would be well positioned to end up as a predator, perhaps devouring Warner Bros Discovery if the share price tumbles. That gives Apple an incentive to settle for terms that the studios cannot tolerate. Streaming video services are a loss leader for Amazon and Apple, lagniappe offered to placate loyal customers while they are fleeced for billions by other parts of the empire. Apple and Amazon could tolerate a significant increase in streaming costs without flinching, just to inflict more pain on rivals like Disney and Paramount.

The old school studios are living on borrowed time. Some of them might pivot into something new for the 21st century but most of them still operate on 19th century industrial principles: totally vertical, they still own the means of production, and that includes vast amounts of real estate, miles of aging soundstages in the center of the most expensive neighborhoods in Los Angeles, warehouses stuffed with flammable sets and flats and props and costumes, staffed by armies of workers. This intensely physical aspect of studio operations runs counter to the prevailing the macro-trend of the 21st century, which is dematerialization.

What the Pessimistic View misses is that the classic movie studios are in serious jeopardy. They are under immense competitive pressure from forces they barely comprehend. Their old mainstay businesses are collapsing. Cinema attendance got whacked during the Covid pandemic and still hasn’t recovered fully. Nobody under 50 watches network TV. Half the nation’s households have cancelled cable TV. Home video is defunct. And they are woefully late to the streaming game, scrambling to pivot to the growth business after a decade of willful ignorance, now pouring money into streaming video services that might never turn a profit in a desperate bid to remain relevant.

So the WGA is not negotiating with one type of entity. It is negotiating with several firms with divergent agendas.

The AMPTP may have be temporarily unified at the bargaining table, but make no mistake about the fact that their goals and desired outcomes vary significantly. Outside of this contract negotiation, they compete fiercely in an unequal battle on a contested playing field.

One more thing: none of the companies negotiating against the Writers Guild are the leaders in artificial intelligence.

Massive tech giants who are not present at the negotiating table will have much to say about how all forms of digital media are created, distributed, discovered, consumed and monetized in the near future.

Regardless of the outcome of the WGA strike, firms like OpenAI, Microsoft, Meta and Alphabet will persist in their reckless AI arms race.

The Writers Guild, and the other talent guilds, the studios, and broadly the entire entertainment and media industry may all end up as collateral damage. They are innocent bystanders, whacked in the crossfire combat to dominate AI.

All of which suggests that any deal that is struck in 2023 will be far less durable than previous pacts, for the simple reason that the media industry is about to go through a massive convulsion (again).

Easy prediction: several leading members of AMPTP will not exist in their current form by 2030.

What if the WGA gets everything they want?

To expose just how profoundly internalized the pessimistic view is, consider the fact that no pundit or columnist has opined about the most optimistic scenario. Everyone seems to assume that the WGA strike will fail.

What happens if the WGA wins?

My take: even if all of the WGA wishes were granted, it would do nothing to solve the big hairy problem, which is the transformation of the broad media ecosystem by generative artificial intelligence.

Even if the writers are granted the guardrails around AI that they seek, it won’t stop or slow the larger trend. Those guardrails will be about as useless as a dike when sea levels surge over the top: they will trap the inhabitants, not protect them.

As a class, professional screenwriters are doomed by generative AI. Not overnight. Not this year. Probably not next year. But certainly by 2030.

Not because there won’t be a need for great screenwriting talent, but because there won’t be a need for a movie studio. We will always need great writers.

In this one respect, the WGA strike is similar to the failed Petition for a Pause that was issued in March. In both cases, the complainant argued for a constraints on progress in AI. For the scientists who signed the petition, it was the impossible dream of a six month moratorium; and for the screenwriters it is a wish for constraints on the use of AI, but in either case the effort is doomed because progress on AI will never stop.

Even if the WGA manages to garner protection for screenwriters within the confines of the motion picture industry, this will have no effect on the huge volume of AI-generated content that occurs outside of union-controlled production.

AI-generated content will soon dwarf the entire catalog of expensive handmade content created by studios.

If it succeeds in negotiations, the WGA might emerge as the master of its domain. But that domain will comprise a dwindling portion of the total media landscape.

AI improves at an exponential pace. As I’ve explained before, this concept is quite difficult for people to comprehend. Also, the volume of content generated by AI increases at an exponential pace. This is like a compound curve within a steep growth curve.

In contrast, traditional TV series and motion pictures scripted by professional screenwriters can only increase at a linear pace, and then only if the budgets increase. That’s a big if.

Eventually the volume of AI-generated content will far surpass the total volume of human-generated work.

Today, generative AI is in its infancy. The output is generally mediocre and easy to dismiss. But we dismiss it at our peril because today’s output is the worst that it will ever be. Each week it gets a little bit better. The pace of improvement is relentless.

The proverbial elephant outside the room at the WGA-AMPTP negotiations is not really a single big creature, it is more like a million mice. Together, they add up to a titanic unstoppable force.

I’m talking about open source AI.

Two months ago, Meta’s LLaMA code leaked into the public domain. It spread like the pandemic. Now thousands of individuals and small teams all over the world are experimenting with it.

Since March, open-source coders have strapped rockets onto the roller skates of innovation. It is now impossible for any individual to keep abreast of all the new product launches. Hundreds of new developments are announced weekly, sometimes daily, each aiming to leapfrog a previous breakthrough.

No contract will shield any part of the motion picture business from the inexorably accelerating rate of AI-fueled innovation.

Consider the following from the past three weeks:

GenAI advertising from Google and Meta

AI movie studios that generate hyperpersonalized content on demand

These concepts range from hypothetical to awkward to amazing. Please resist the impulse to dismiss them. Remain seated with your seatbelt fastened and watch this space. Turbulence is expected.

I could list hundreds more examples in this vein, but like I wrote above, keeping track of every innovation in this space is a mug’s game. Suffice to say, if you can imagine it, it’s being developed right now, probably by multiple competing teams.

If you are still not convinced that artificial intelligence will soon be capable of generating compelling and persuasive narratives, just read this scary thread on AutoGPT. Then go outside for some fresh air.

A personal anecdote on a human scale. A few weeks ago, I was a judge in a one-day movie hackathon held at the University of Nebraska’s Johnny Carson Center for Emerging Media Art.

The students began working at 9 AM on a Saturday morning with no more than instructions to generate a script for a 3-minute film using ChatGPT. Next, they generated images to accompany their scripts, using tools like Midjourney. Then they used other AI tools to animate the characters, render motion video sequences, generate character voices with dialog and crank out soundtracks. By the 6 PM deadline, seven teams had submitted 3-minute films, complete with music and titles. Almost 100% of these films were generated by artificial intelligence.

The films weren’t great. They were student films, after all. But they were complete, coherent linear narratives, all original and generated by AI.

From script to a final cut, mixed and titled, all done in a single day.

To paraphrase Dr Johnson’s quip to Boswell,

“Sir, AI generated films are like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.”

The tools will improve. So will the students. Then they will graduate and enter the workforce as one-person production companies. They will have the option to replace each phase of filmmaking (screenwriting, pre-production ideation and visualization, principle photography, and post production) with software that renders results in moments.

Will they still use traditional filmmaking techniques? Sure, why not? If they choose to. The past is optional. They will have at their disposal a vast range of choices, which include all traditional techniques plus a growing spectrum of novel AI applications. All of it deployed in the service of delivering a final film at a small fraction of the amount spent by a movie studio to accomplish the same result.

When they graduate, these Carson Center students will be equipped with two superpowers that neither the WGA members nor the AMPTP seem to possess: fluency and agency in the technological vernacular that will redefine video entertainment forever.

My own professional experience during the past three months has been like trying to get a drink from the proverbial fire hose. It is exhilarating. I’ve been pitched more than a hundred AI concepts by entrepreneurs across the country, ranging from AI-supported campaign generators to an AI-powered ad agency and even a fully autonomous motion picture studio. Fourteen different organizations across the US have invited me to help them with AI strategy, and I am now engaged in discussions with enterprises as far away as Asia and Africa.

This is no boast. My experience is hardly unique. It’s not special in any way: this is the tenor of our time. There are literally millions of similar discussions happening every day in every corner of the planet right now. If you and your colleagues are not talking about how AI will transform your business, you’re behind.

The proliferation of this technology, and the resultant acceleration of innovation, leaves me astonished and inspired. From my viewpoint, the WGA-AMPTP standoff appears to be taking place in a bubble while a massive tornado rages around it.

This article is the third in a series about artificial intelligence and the WGA strike. If you have not read the full series, please check it out here.

In my next newsletter, I will turn my attention to the other factors that will reshape the media ecosystem and other parts of the economy: AI versus copyright and the ascendancy of algorithms.

Brilliant 👏…and sobering 🫣